flowchart LR

A[1. Focus on<br/>Wildly Important] --> B[2. Act on<br/>Lead Measures]

B --> C[3. Keep a<br/>Scoreboard]

C --> D[4. Weekly<br/>Accountability]

D --> A

Introduction

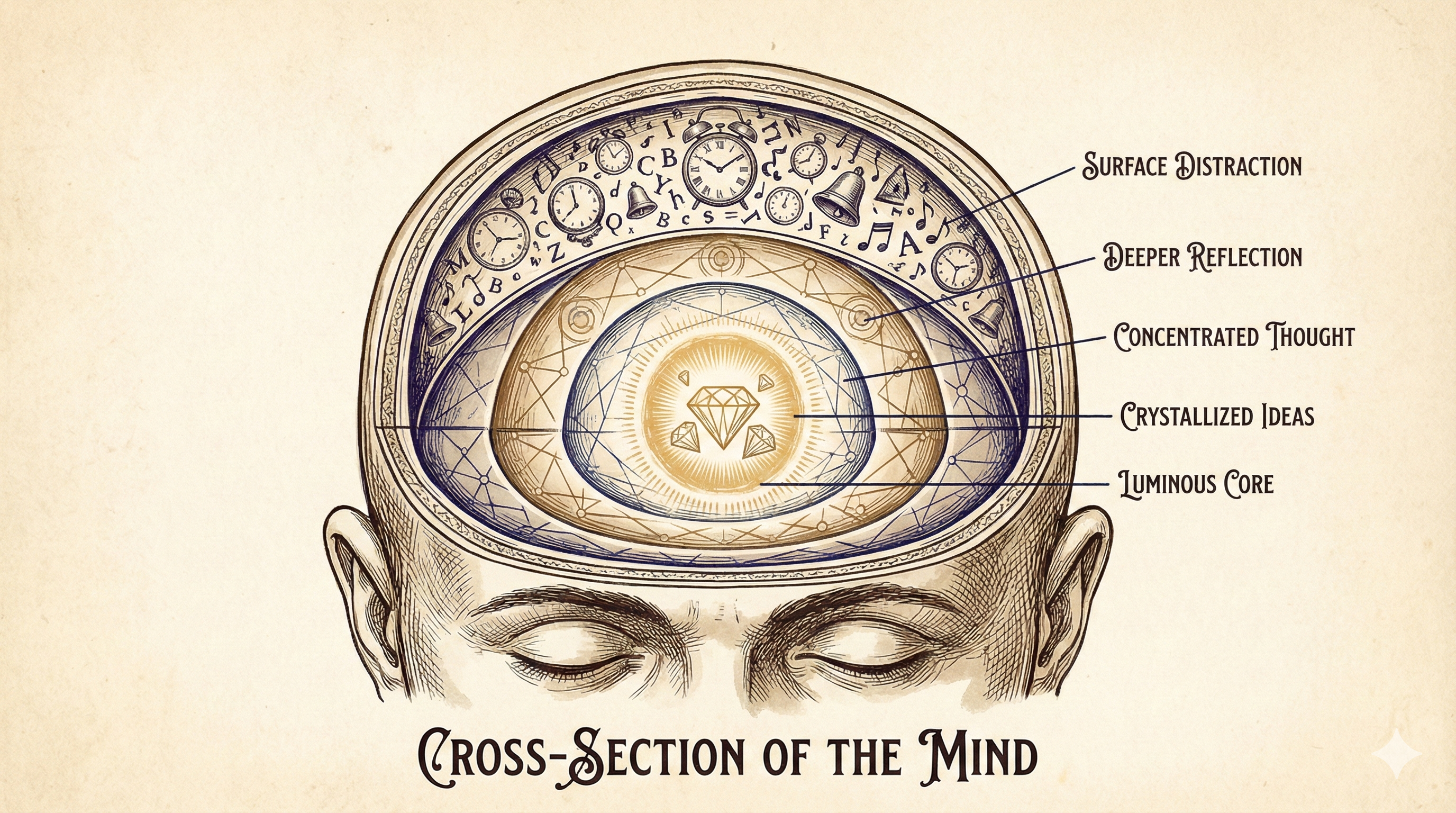

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skills, and are hard to replicate.

Shallow Work: Non-cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks often performed while distracted—answering emails, attending status meetings, filling out forms.

We live in a knowledge economy where people are rewarded for the valuable things they produce rather than the hours they clock. The more complex and valuable your output, the more you’ll thrive. This creates two core abilities that are becoming increasingly valuable:

The ability to quickly master hard things. Technology changes rapidly, which means learning never ends. Whether it’s a new programming language, statistical technique, or domain expertise, you must be able to acquire complex skills efficiently.

The ability to produce at an elite level, in both quality and speed. Mastering the fundamentals isn’t enough. You need to take that knowledge and produce something novel, complex, and valuable with it.

Both abilities depend on your capacity for deep work. Deliberate practice—the kind that builds expertise—requires intense, focused attention on the specific skill you’re trying to improve. You can’t learn hard things or produce exceptional work while constantly distracted.

This leads to Newport’s central argument: deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it’s becoming increasingly valuable. Those who cultivate this skill will thrive.

The Deep Work Hypothesis

\[\text{High-Quality Work Produced} = \text{Time Spent} \times \text{Intensity of Focus}\]

This equation has profound implications. If you spend four hours working with half your attention on email and Slack, you produce far less than someone who works two hours with complete focus. The intensity multiplier matters enormously.

The reason is neurological. When you switch tasks, your attention doesn’t immediately follow—a phenomenon researcher Sophie Leroy calls attention residue. Part of your mind keeps thinking about the previous task, especially if it was left incomplete.

Every time you glance at your inbox, check a notification, or respond to a quick message, you leave attention residue that degrades your performance on your primary task. Multitasking is a myth for cognitively demanding work—you’re rapidly switching between tasks and paying the attention residue tax each time.

Why Deep Work Is Rare

Despite its value, deep work is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve in modern workplaces. Several trends push in the opposite direction.

Open office plans were designed to increase collaboration and serendipitous interaction. The reality has been different. Studies, including research from companies like Google that pioneered open offices, show that productivity doesn’t necessarily increase. Employees in open offices send more emails and instant messages than before—even to colleagues sitting nearby—because they lack the privacy for focused conversation. The constant visual and auditory distractions make sustained concentration nearly impossible. The more cognitively demanding your work, the more you suffer in such environments.

Always-on communication expectations compound the problem. Many organizations expect employees to respond to emails within hours, if not minutes, including evenings and weekends. This creates a state of constant task-switching that fragments attention throughout the day. Managers often push work to their teams through quick emails rather than investing time to figure things out themselves—it’s easier to ask than to think.

Meetings proliferate without clear purpose. Many meetings don’t solve problems or lead to decisions; they exist because meeting feels like work, even when it isn’t.

Why do organizations tolerate these productivity-killing practices? Because the impact of deep work is hard to measure. Unlike widgets produced or calls answered, you can’t easily quantify the difference between a mediocre solution and an elegant one, or between shallow busyness and genuine insight. In the absence of clear metrics, organizations default to visible activity as a proxy for productivity. Looking busy becomes more important than being productive.

The good news is that this creates an opportunity. If you can cultivate deep work while others flounder in shallows, you gain a significant competitive advantage.

The Meaning of Deep Work

Beyond productivity, deep work offers something deeper: meaning.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research reveals that the best moments in our lives occur when we stretch our minds or bodies to their limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Ironically, free time is often harder to enjoy than work because it lacks structure and requires more effort to shape into something satisfying.

What we choose to focus on shapes who we become. Our thoughts, feelings, character, and loves are largely the sum of what we pay attention to. When we’re scattered and distracted, our minds tend to fixate on what’s wrong in our lives. Deep concentration crowds out this negativity—there’s simply no attention left for worry when you’re fully absorbed in challenging work.

Deep work also transforms how we relate to our professional lives. When you approach your job with the mindset of a craftsman—someone who dedicates focused effort to honing their skills and producing quality work—even ordinary jobs can become sources of meaning and satisfaction. The satisfaction comes not from the nature of the work itself but from the approach you bring to it.

Rule I: Work Deeply

Willpower Is Limited

A key insight from psychology is that willpower is finite. You can resist checking your inbox or social media for a while, but as the day wears on, your willpower depletes. Eventually, you give in. This is why relying on willpower alone to maintain focus is a losing strategy.

The solution is to build routines and rituals that minimize the need for willpower. Instead of deciding each moment whether to focus, you make the decision once and let habit carry you forward.

Choose Your Depth Philosophy

People have different work constraints, so Newport identifies four approaches to scheduling deep work:

| Philosophy | Description | Best For | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monastic | Eliminate nearly all shallow work | Those with singular, well-defined professional goals | Donald Knuth (no email) |

| Bimodal | Alternate between extended deep periods and normal work | Academics, writers with flexibility | Carl Jung (retreat weeks) |

| Rhythmic | Same time daily, every day | Most people; builds habit | 5-7 AM daily block |

| Journalist | Fit deep work whenever possible | Experienced practitioners only | Cal Newport |

For most people, the rhythmic approach is most sustainable. Use the chain method (popularized by Jerry Seinfeld): mark each day you complete your deep work session with an X on a calendar. Your goal becomes maintaining the chain—the visual progress motivates consistency.

Build Rituals

Effective deep work requires more than scheduling. You need rituals that reduce friction and decision-making:

Where and how long: Have a dedicated location for deep work if possible. Decide in advance how long the session will last—open-ended sessions invite procrastination.

Rules during the session: Define what’s permitted. No internet? No email? A specific number of words or problems to complete? Clear rules prevent internal negotiation.

Support needs: Prepare what you need before starting—coffee, water, materials, snacks. A walk before the session can help clear your mind. Removing logistics from the session preserves mental energy for the work itself.

Grand gestures can also help. Changing your environment—working from a library, cabin, or coffee shop—signals to your brain that this session matters. The investment of effort and possibly money in reaching this new location creates psychological commitment that helps overcome procrastination.

Collaboration and Deep Work

Deep work doesn’t mean working in isolation. Collaboration remains valuable for learning, getting feedback, and generating ideas through discussion. The key is to separate collaboration from deep work rather than mixing them constantly.

The most productive approach alternates between the two: collaborate to identify problems and share perspectives, then retreat into deep work to develop solutions. Whiteboarding with colleagues can spark insights, but implementing those insights requires solitary concentration.

Execute Like a Business

Newport draws on The 4 Disciplines of Execution to make deep work more systematic:

Focus on the wildly important. Identify a small number of ambitious outcomes that deep work can help you achieve. Having too many goals dilutes your focus.

Act on lead measures. Lag measures (like papers published or revenue generated) tell you if you’ve succeeded, but they’re not actionable in the moment. Lead measures track behaviors you can control that drive results. For deep work, the key lead measure is time spent in deep work dedicated to your wildly important goal. Track hours, not outcomes.

Keep a compelling scoreboard. A visible record of your deep work hours creates motivation. It can be as simple as a paper calendar where you log daily hours. Watching the numbers accumulate reinforces commitment.

Create a cadence of accountability. Review your scoreboard weekly. Celebrate good weeks. For bad weeks, analyze what went wrong and plan adjustments. This prevents a single bad day from becoming a bad month.

Embrace Downtime

Research on unconscious thought suggests that complex decisions benefit from periods of incubation. Your unconscious mind has more processing capacity for sorting through complex, ambiguous information. By stepping away from a problem and letting your unconscious work on it, you often return with better insights than if you had consciously ground away.

More practically, attention is a finite resource that depletes with use. Studies show that exposure to nature replenishes directed attention—a walk through a park restores focus more effectively than a walk down a city street, because natural environments engage attention gently rather than demanding it. Any activity that frees you from directed attention—prayer, meditation, casual conversation, exercise—helps restore your capacity for focus.

This has direct implications: evening work is often counterproductive. After a full day, you’ve typically exhausted your deep work capacity anyway—experts max out around four hours daily, beginners far less. Working in the evening just burns attention reserves you need for tomorrow.

Create a shutdown ritual to end your workday cleanly:

flowchart TD

A[End of Workday] --> B[Review inbox for<br/>urgent items]

B --> C[Scan task list<br/>and calendar]

C --> D[Make rough plan<br/>for tomorrow]

D --> E["Say 'Shutdown Complete'"]

E --> F[Rest with<br/>clear mind]

This ritual gives your mind permission to release work concerns. Without it, incomplete tasks linger in your thoughts—the Zeigarnik effect—and prevent true rest.

Rule II: Embrace Boredom

Deep work is a skill, not a habit. Like any skill, it improves with practice and atrophies with neglect.

Here’s the problem: if you constantly seek stimulation whenever you feel even slightly bored—pulling out your phone while waiting in line, scrolling social media during any idle moment—you’re training your brain to require constant novelty. This training has lasting effects. Your working memory becomes cluttered with irrelevant information, and your ability to filter distractions weakens. When you finally try to focus, your brain rebels.

Building deep work capacity requires training two distinct abilities:

- Improving your ability to concentrate intensely

- Overcoming your desire for distraction

Schedule Internet Blocks

One powerful technique is to schedule specific times when you’re allowed to use the internet, and stay offline the rest of the time. This is the opposite of scheduling internet breaks during focused work—instead, you schedule focus breaks during an otherwise offline day.

- Schedule specific times for internet use (e.g., 10-10:30 AM, 1-1:30 PM)

- Stay offline outside these blocks—no exceptions

- If blocked on a task, work through it or switch to another offline task

- The goal: train your brain that it doesn’t get stimulation on demand

Roosevelt Dashes

Theodore Roosevelt, despite his many extracurricular activities at Harvard, graduated Phi Beta Kappa by working with intense concentration during limited study periods. You can train similar intensity through what Newport calls “Roosevelt dashes.”

Identify a deep task that’s important and estimate how long it would normally take. Then set a hard deadline significantly shorter than that estimate—short enough that you can only succeed through intense focus. Use a timer. Allow no distractions. Attack the problem with everything you have.

Try this experiment once a week, progressively shortening the deadline. Over time, you’ll train your brain to work with greater intensity.

Productive Meditation

Use periods when you’re physically occupied but mentally free—walking, commuting, showering, exercising—to focus on a single professional problem. Newport calls this productive meditation.

flowchart TD

A[Choose one<br/>professional problem] --> B[Define key variables<br/>of the problem]

B --> C[Identify next question<br/>to answer]

C --> D{Attention<br/>wanders?}

D -->|Yes| E[Gently redirect<br/>to problem]

E --> C

D -->|No| F{Mind<br/>looping?}

F -->|Yes| G[Push toward<br/>harder parts]

G --> C

F -->|No| H[Consolidate gains:<br/>review reasoning]

Productive meditation strengthens two skills simultaneously: your ability to resist distraction and your capacity for deep thinking. Results may be modest at first, but persist—the benefits compound over weeks.

Memory Training

An unexpected way to improve concentration is memory training. Research on mental athletes—people who compete in memorizing decks of cards or strings of digits—shows they develop superior attention control. The intense focus required for memorization strengthens the same neural circuits used in deep work.

Any systematic memorization practice can provide this benefit—memorizing poetry, scripture, speeches, or using memory palace techniques. The content matters less than the sustained, focused attention the practice requires.

Rule IV: Drain the Shallows

Even with the best intentions, shallow work fills available time like gas expanding to fill a container. Without deliberate constraints, email, meetings, and administrative tasks will crowd out deep work entirely.

Time-Block Your Day

Plan every minute of your workday in advance. Use a notebook or digital tool to divide your day into blocks of at least 30 minutes each, assigning specific tasks or types of work to each block.

This isn’t about rigidly following a schedule—interruptions and changing priorities are inevitable. The point is intentionality: deciding in advance how you’ll spend your time rather than reacting to whatever seems urgent in the moment. When your plan breaks down, take a few minutes to revise it. The act of planning, not the plan itself, is what matters.

Time-blocking forces you to confront how you’re actually spending your day. Most people are shocked to discover how little time remains for deep work once meetings, email, and miscellaneous tasks are accounted for.

Quantify the Depth of Every Activity

Not all tasks are equally shallow or deep. To evaluate where your time goes, Newport suggests a simple heuristic:

Ask: How long would it take to train a smart recent college graduate to do this task?

- Weeks = Shallow (scheduling, basic correspondence, data entry)

- Months/Years = Deep (complex analysis, creative work, strategic thinking)

Use this metric to audit your workday. If shallow tasks dominate, you need to restructure. Push back on demands for shallow work or find ways to batch and minimize it. Protect your deep work blocks aggressively.

Fix a Firm Finish Time

Parkinson’s Law holds that work expands to fill the time available. Combat this by committing to end work at a fixed time—say, 5:30 PM—and working backward to ensure you finish what matters.

This creates productive urgency. Knowing you can’t work late forces ruthless prioritization: shallow tasks get compressed or eliminated, and deep work gets protected because it’s the only way to complete important projects.

A fixed finish time also supports the shutdown ritual and downtime that restore your capacity for deep work tomorrow.

Tame Email

Email is perhaps the most insidious source of shallow work. A few strategies can reduce its grip:

| Strategy | How It Works |

|---|---|

| Make senders do more work | Use different addresses for different purposes; set auto-responders with expectations |

| Process-centric responses | Think through the entire exchange; close loops in one message |

| Don’t respond | Silence is acceptable for ambiguous or low-stakes messages |

Bad: “When would you like to meet?”

Good: “I’m available Tuesday 2-4 PM or Thursday 10 AM-noon. If either works, let me know and I’ll send a calendar invite. If not, please suggest three alternatives.”

The goal: minimize back-and-forth by thinking through the entire process upfront.

Conclusion

Deep work is the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. It’s a skill that produces valuable output and creates meaning in professional life.

Yet it requires what many are unwilling to give: the discipline to resist easy distraction, the patience to build concentration through practice, the intentionality to protect your time from shallow demands, and the courage to step back from the constant connectivity that defines modern work.

- Work deeply — Build rituals and routines; don’t rely on willpower

- Embrace boredom — Train your brain to resist constant stimulation

- Quit social media — Apply the craftsman approach to tool selection

- Drain the shallows — Time-block your day; protect deep work aggressively

The deep life is not for everyone. But for those willing to pursue it, the rewards are substantial: the ability to learn quickly, produce quality work, and find satisfaction in pushing your mind to its limits. In a world increasingly dominated by distraction, the capacity for sustained focus becomes ever more rare—and ever more valuable.